Golf Nuts – This is a story that any golf nut would enjoy reading, especially a golf architecture nut! – The Head Nut (#0001)

By Josh Berhow, Golf.com

It’s March 2, 2018, and Mike Manthey is sitting at his desk. Manthey is the superintendent of Midland Hills Country Club in St. Paul, Minn., and his office is a part of the addition that was built on to the maintenance facility in 1991. He has posters and pictures on the walls, dozens of books behind him and a couch in front of him. In the closet to his left, which is filled with boots, tools, hats, maps and filing cabinets, one of the ceiling tiles is slightly dislodged, revealing a gap of an inch or so, enough to be noticed but never a nuisance. It’s been like this for years. For whatever reason, Manthey decides today is the day he’ll finally repair it.

He pulls up a chair, steps on to it and pushes the tile aside. Peering through the opening, he spots what appears to be a rolled-up map against the wall. He retrieves it, brings it back to his desk and knows immediately that it has been up there for many years — canvas maps of this type haven’t been made for decades. Manthey places the drawing on the floor of his office and peels open a corner.

You got to be kidding me, he thinks. Is this really what I think it is?

The creation of Midland Hills

Before understanding why Manthey’s discovery was so significant, it is important to understand how Midland Hills arrived at that moment. Member John Hamburger caddied at the club in the late ’60s and was club president from 2004-06. Between Hamburger’s own experiences and extensive research — he has pored through archives of club minutes, newspapers and books — few know more about Midland Hills than its unofficial historian. But somehow, two items had always eluded him, believed to be lost over time: the founding club’s history from the 1920s, and architect Seth Raynor’s original course map.

The map, Hamburger says, was mentioned in club documents, but he never had any luck finding it, despite exhaustive searches. Chances he ever would unearth it took an ominous turn in 2003, when George Bahto visited. Bahto was an expert on the lives and design careers of giants C.B. Macdonald and Raynor; he wrote the design biography The Evangelist of Golf: The Story of Charles Blair Macdonald and, up until his 2014 death, was working on a design biography of Raynor. Interested in learning more about its past, Midland Hills hired Bahto to review the property, which led to his visit. During his tour, Bahto said Raynor never kept much from his projects, so he doubted he would have held on to the routing. It was more than likely gone.

According to Hamburger, the original site of Midland Hills — University Golf Club — officially opened in the spring of 1916 after a group of University of Minnesota staffers set out to create a club with a nine-hole golf course near campus. The initial five-year lease wasn’t extended, and the club leased two large pieces of land (about 160 acres total) just north of the club in 1919. According to club minutes, 45-year-old Tom Vardon, the head pro at White Bear Yacht Club and brother of six-time Open Championship winner Harry Vardon, was asked to survey the land. He visited in January 1920 and, despite seeing a course covered in snow, was “enthusiastic over its possibilities.”

Now all he needed was an architect.

How could this have possibly happened, and 100 years later?

Raynor was born in Manorville, N.Y., in 1874, and worked as an engineer mostly on Long Island. In 1908, Macdonald hired Raynor for a boundary survey on the property that would become iconic National Golf Links of America. Raynor and Macdonald hit it off and started working together on all of Macdonald’s designs. By 1914, Raynor had his own projects.

In 1920, about 12 miles southeast of where the Minnesota group had just leased land for its new club, on the other side of the Mississippi River, Raynor was building Somerset Country Club, in Mendota Heights, Minn. Because he was in the area — and because the club deemed Donald Ross too expensive — the group talked Raynor into touring the property, the land that would become Midland Hills. Satisfied, Raynor agreed to come aboard for $1,500. He said he’d lay out the course on a model, just as long as the club would deliver him a contour map within three weeks. It would become one of just a handful of Midwest courses Raynor designed.

“Midland really just came in as what we joke about as a two-fer,” Hamburger says. “We got very lucky.”

On July 15, 1920, construction began. Ralph Barton, a math professor, supervised a team of 33 men and three teams of horses, moving rocks, shaping tees, digging bunkers. Even club members pitched in. A farmhouse — white with green trim — became the clubhouse, and the course officially opened for play on July 23, 1921, changing its name to Midland Hills Country Club in April 1922. Initiation fees were $50 and guests could play for 50 cents on weekdays. (The nearby 9-holer where the lease was not renewed has since been renovated and is now the University of Minnesota Les Bolstad Golf Course.)

Midland Hills bought the land upon which it sits in 1947, and the course routing changed in 1960 when the new clubhouse was built. Another new clubhouse and course renovation came in 2001, and the course was lengthened in 2005. But bigger changes were coming.

The birth of a Raynor restoration

Manthey took the head superintendent job at Midland Hills in 2010, after 10 years at nearby Golden Valley Country Club. The Minnesota native, now 41, like many supers, is a golf-course architecture enthusiast. There’s pride that comes with working at one of the few Raynors in the region.

Indirectly, the club’s latest restoration stemmed from an ill-suited bunker on the par-4 1st. The bunker just never seemed to fit. The green didn’t either, actually. It spiraled from there. If we restore that bunker, Manthey and committee members thought, why not rebuild the green back to a more classic look, too? These conversations began in 2014.

“Then it turned into, If we do that to this hole alone, and really put it back to Raynor architecture, now we’re going to have one hole that’s going to look different from the other 17,” Manthey said. “So it morphed into, Maybe we need to bring in somebody that really understands Raynor architecture, and we can do this formally.”

CLICK THROUGH TO SEE BEFORE AND AFTER PHOTOS OF ALL 18 GREENS:

Jim Urbina was the co-architect at Old Macdonald at Bandon Dunes and has led many other Golden Age restorations, including one he finished on another Raynor course in Charleston, S.C. — Yeamans Hall. (Coincidentally, old Raynor maps found in the clubhouse attic in the 1980s helped guide that restoration, too.) Manthey first met Urbina by chance at Los Angeles Country Club in 2013. They kept in touch, often times discussing Midland Hills and the intricacies of Raynor designs.

Eventually, Manthey told Midland Hills general manager Tim Ivory that he’d like to bring in Urbina to check out the property. Manthey wasn’t even sure how many Raynor template holes Midland Hills had. He knew of some, but trees obscured much of the original design. Plus, Midland Hills’ earliest aerial map was from 1937, 16 years after the course debuted. No one knew how much the routing changed in those early years. Urbina was originally skeptical of Raynor’s involvement since few Raynors existed outside of the East Coast, so in 2015 he came in and toured the property with some staff and a small group of members. Manthey remembers Urbina seeing potential in the course and saying, most important, there was “a lot of Raynor here.”

Early in 2018, Urbina officially agreed to lead the restoration. The master plan was to break ground in 2020 and unveil the course in 2021, when it was celebrating its 100th year of play. Urbina and Manthey promised to restore what remained of Raynor’s routing and features from 1921. Urbina’s goal was to have members think they stepped on a Raynor course as it was in the 1920s, enjoying a game of golf, as intended, on a Golden Age course lost in a world of modern designs.

When Urbina officially joined the project, neither he nor Manthey knew of any map. That was all about to change.

‘I think I found something pretty special’

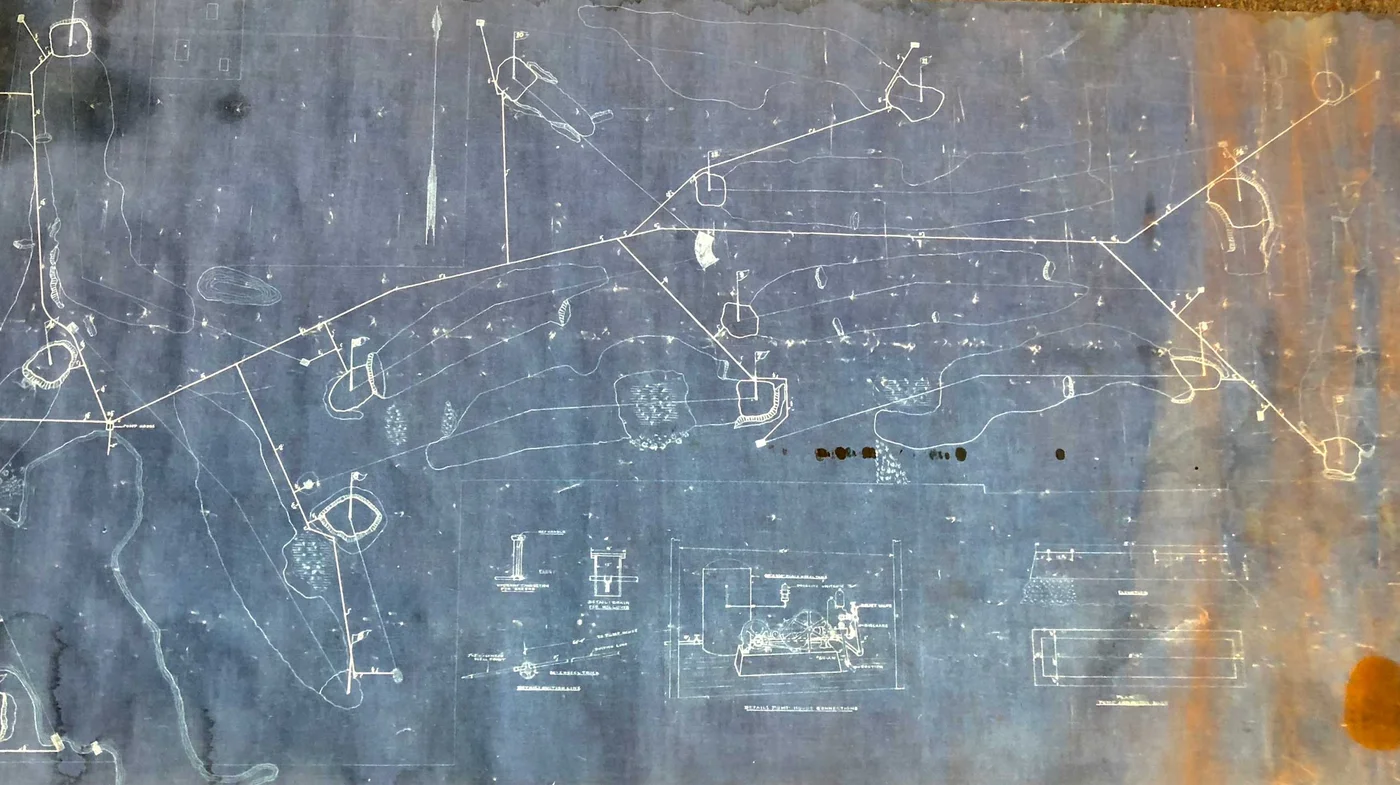

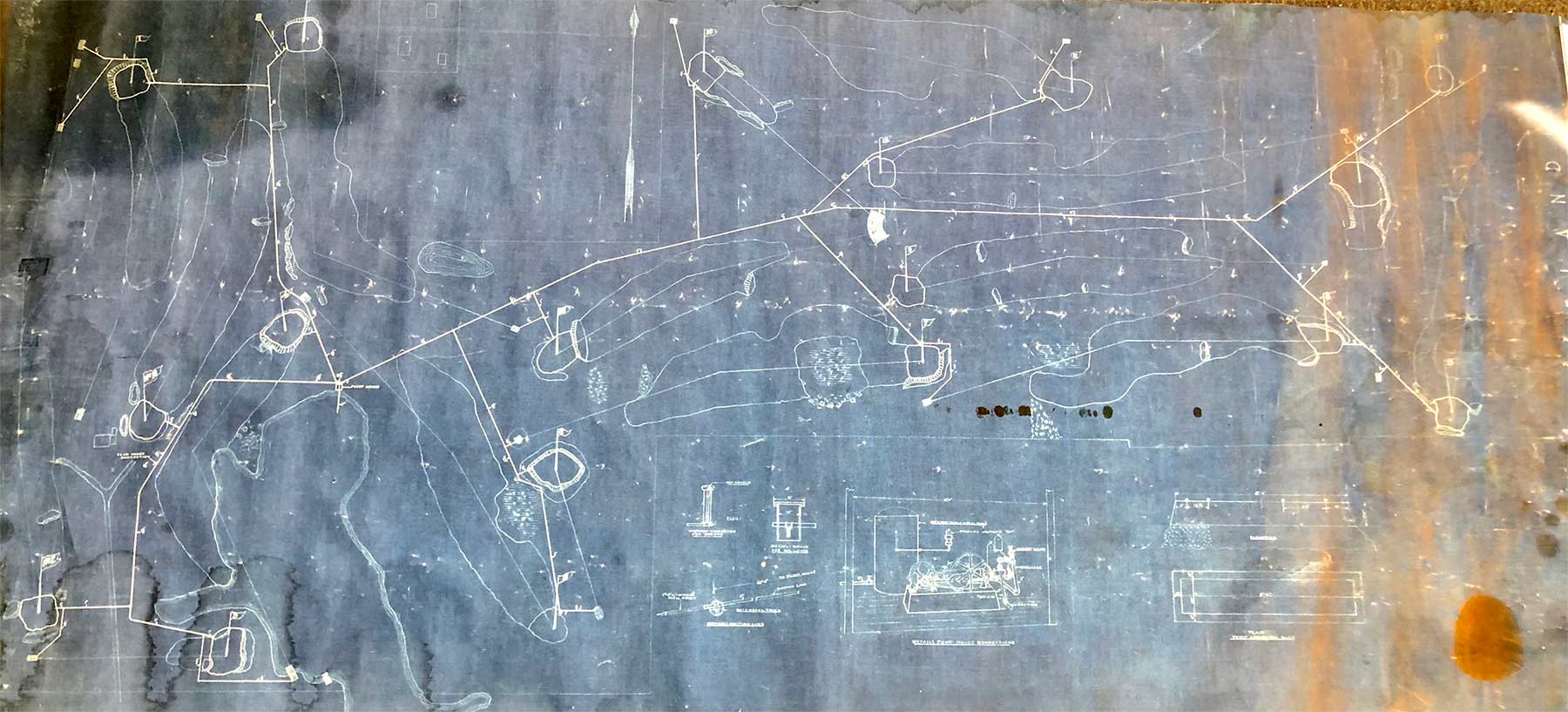

As he carefully unfurled the map on that March day in 2018, Manthey was stunned. With each inch that he revealed of the 6-foot-long canvas, he came closer to confirming his initial hunch. That’s his course. Midland Hills. As it once was.

He rolled the map out on the floor and stood back. Before him was a detailed blueprint of Raynor’s original design with the club’s first irrigation system sketched on top of it. He beckoned his assistant, Mark Ries.

“I said, ‘You gotta come in here and look at this. I think I found something. I think I found the map,’” Manthey said. “He walked in the door and was like, ‘Holy s—.’”

Manthey couldn’t stick around long — he had to take his kids to gymnastics practice — but he snapped some photos and sent the best ones to Ivory, the general manager; head pro Ryan Hanford; and Hamburger. “I think I found something pretty special,” he texted them. They called him immediately. He then sent a photo to Urbina, who was floored. He was already studying the document, taking zoomed-in photos of bunkers and green shapes and commenting on fairways, angles and more.

“I could hardly wait to get back to St. Paul and look at it,” Urbina said. “And when he showed it to me, and I touched it, I was like, ‘This is creepy, man.’ It’s creepy in the sense that for someone like me who relishes and cherishes Golden Age design and the history that goes with them, to actually touch a map that Raynor had worked on and been a part of — you could understand my mesmerization.”

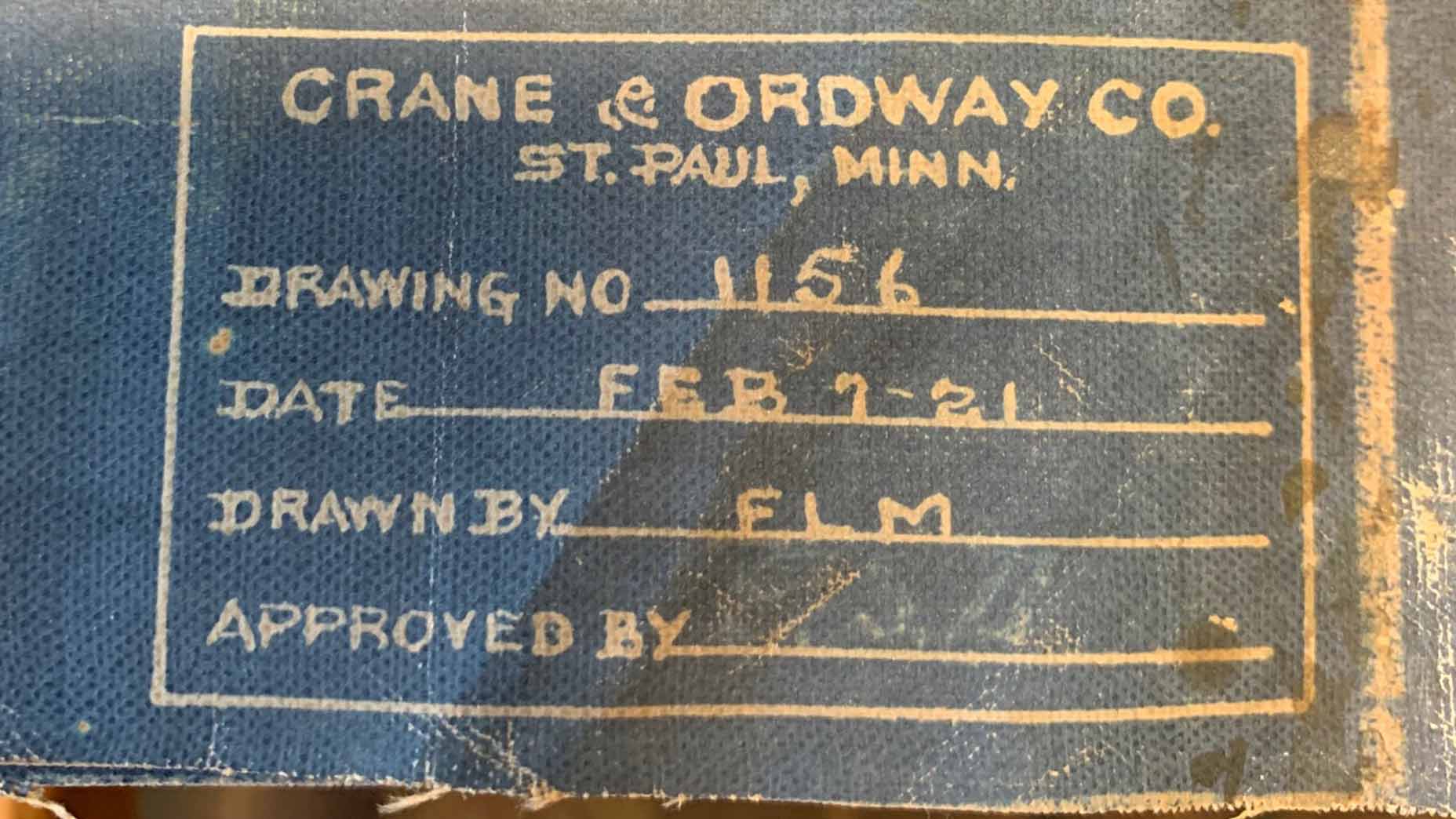

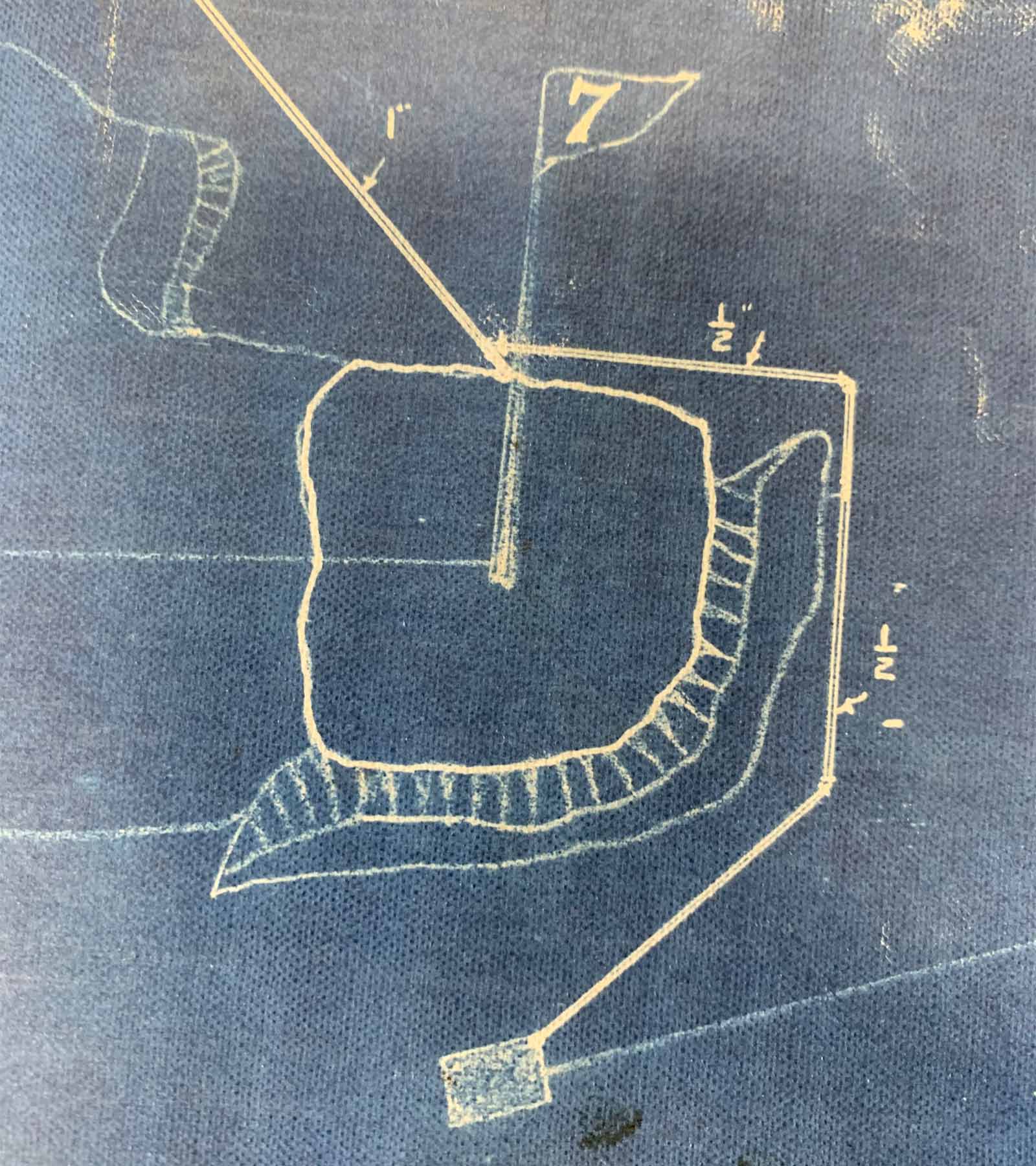

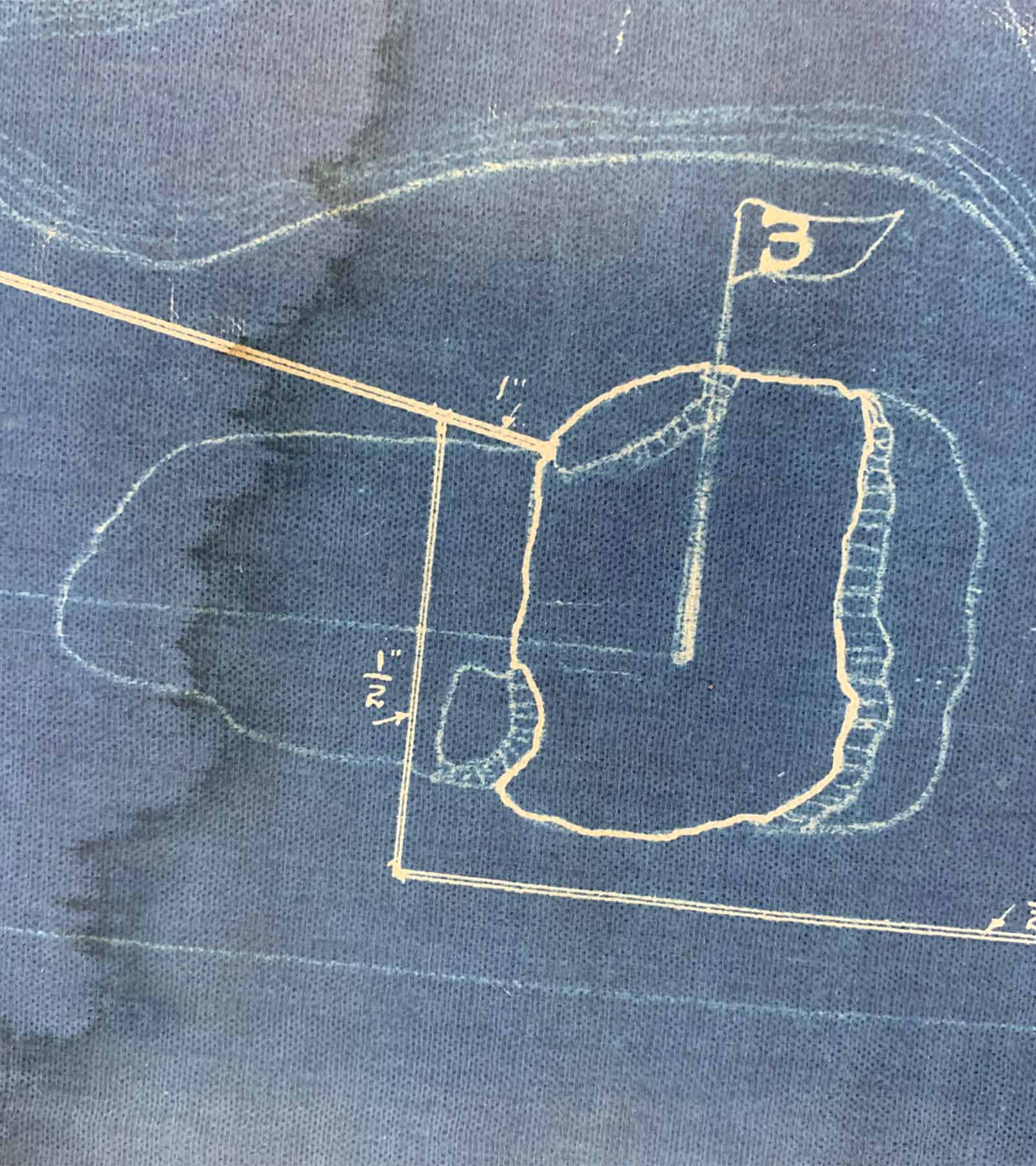

A framed copy of the map now hangs in the entryway of the clubhouse. The original smells musty, is a touch discolored and has several stains — coffee, ink or oil, maybe mud or grease — but is in remarkable condition given its age. The detail is astonishing, handmade with a special chalk. There are diagrams of an irrigation pump and pumphouse connections and, as Manthey points out, the design is so precise that the irrigation pipes are actually two lines with just the slightest gap in between, maybe a millimeter, showing that they are hollow. One corner of the back of the map says it was made by Crane & Ordway Co., a St. Paul company. Its drawing number is 1156, dated Feb. 7, 1921. It’s almost 100 years old.

“Finding this map did two things,” Manthey said. “We already knew we were a Raynor, but it cemented the fact that this was a Raynor. And now we have something physical that shows this was Raynor’s routing, which is really cool. A lot of clubs don’t have that.”

It’s believed the map was packed away somewhere in the clubhouse and moved to the maintenance facility when the new clubhouse was built in 1960. After the maintenance facility addition had been completed, someone stashed the map in the closet ceiling. The super there at that time told Manthey he doesn’t remember putting anything up there.

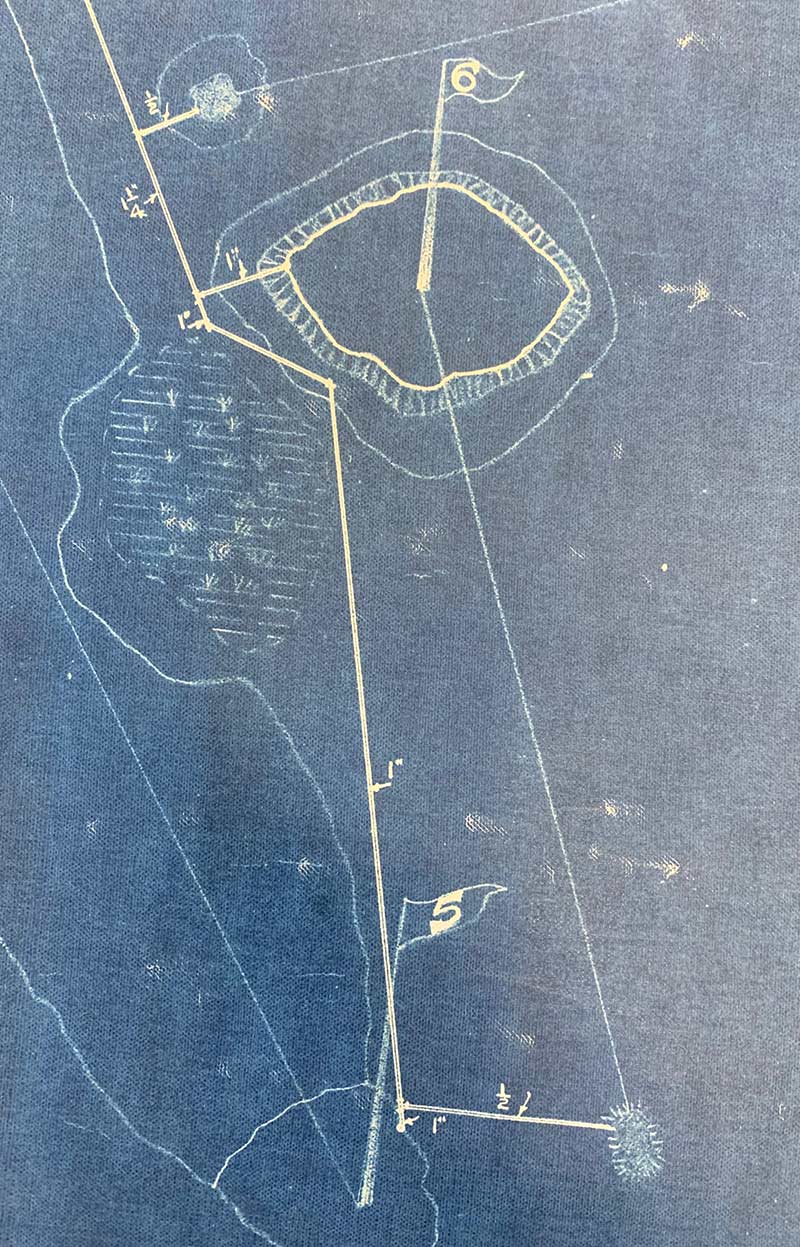

Finding Raynor’s map never meant the course would be rebuilt exactly as it was 100 years ago — not with a multimillion-dollar clubhouse in the way — but that was never the plan. Fifteen of the 18 holes at Midland Hills are originals, albeit with tweaks over the years. The routing changed after the new clubhouse was built in 1960. The 6th hole, a Short template, was moved and rebuilt where the old clubhouse and range were, and is now the 4th hole. The 7th and 16th that ran through the middle of the course were also removed (that’s where the driving range sits today), and new 1st and 18th holes were built.

The plan for this project was to restore what remained of Raynor’s routing and features. But the map did provide some extraordinary detail that was highly beneficial — not to mention fascinating — for Manthey and Urbina.

“We said, ‘Jim, take your knowledge of this golf course, of what the map has, and you come up with what you think would be the best golf course,’” Manthey said.

The map included locations of all the original cement hydrant connections that were located next to the greens and tees. The crew dug up three of them, and those, along with some of the original pipes found around the greens, helped confirm that the map and size of the property was to scale.

But there were even more hidden treasures — like bunkers. The 2nd, a par-4 Road Hole template, had a right fairway bunker in a 1937 aerial map (the earliest map the club had), but that was buried at some point, likely in the 1940s. But the 1921 map showed an original bunker, the Scholar’s bunker, on the left side of the fairway, where it should be for a Road template. The crew scouted where they thought it might be, and Urbina painted an area where sod should be removed. They dug, found the original sand and rebuilt the bunker as it was intended. This happened four different times, with the map showing bunkers unknown to them, and the crew finding and restoring them.

“The map just helped us confirm locations, fairway, widths, pipes — it was just like a gold mine of treasures that were found based off this map,” Urbina said. “How could this have possibly happened, and 100 years later?”

The project’s main shapers were Zach Varty and Joe Hancock. When they found the first trace of something that was original, the crew stopped and took pictures. A mini celebration of sorts.

“For 100 years we were walking over the top of it; you’re finding history,” Manthey said. “So stuff like this was really cool, because appreciating history, and really studying everything that we had, aerials and the map, and finding something like this in the field was really cool. Even to a guy like Jim, it was a big deal.”

Builders broke ground on the restoration on July 20, 2020, and the course was closed two weeks later. Every tee was rebuilt, repositioned and realigned, and every bunker (50 of them) was rebuilt and filled with new sand. Some bunkers discovered from the map were dug up and restored. New drainage was installed, and parts of cart paths removed. The greens were expanded by nearly one acre, and the fairways were enlarged by more than five acres. About 3,000 yards of soil was removed during the entire project, most of which taken from around the greens and to lower tees. Thirty acres of rough was converted to fescue, both for strategic and aesthetic reasons, the latter to accentuate the topography, which Manthey says is the rolling property’s biggest asset.

The scale of the property is much more visible now, too, and has been since Manthey started removing trees years ago. He’s taken out between 1,200 and 1,500 trees over the last 15 years to bring back Raynor’s intended sightlines and strategies. From the 9th tee, for example, you can now see every green on the front nine. Identifying all of Raynor’s templates years ago might have been difficult. Now, Midland Hills has 14 of them. Even the two new holes (1 and 18) built long after Raynor died incorporate his design characteristics to seamlessly integrate into the routing.

Proof that early reviews are positive: Midland Hills added 20 new members in the fall — joining a club with a course they couldn’t even play until next year.

“Younger players, they don’t care about the hot dogs and cold beer,” Manthey said. “Everybody’s got that. Architecture, if you have it properly presented, really gives you a unique asset to market. And that was a huge part of this project, and not just for current members. Our board of directors and our leadership at the club, they were smart enough to say, ‘We’re doing this for us, but we’re also doing this for future generations,’ which was really cool.”

The new Midland Hills

It’s an unusually warm December Wednesday in Minnesota, perfect for a stroll. The Minneapolis skyline glimmers in the distance as Manthey twirls a water bottle and walks the 18th fairway to the new-look 18th green at Midland Hills. The bunker guarding the left side was completely overhauled and reshaped, a back bunker was added to collect any long shots and the green shape itself reverted to a more classic Raynor design with squared-off corners. Manthey’s two-and-a-half-year-old Terrier/Border Collie mix, Oli, tags along, occasionally pausing for a sniff or to grab a stick. Oli, besides being a loyal companion, helps with the geese. “She chases anything with legs,” Manthey says.

During a two-hour tour of the property, Manthey recounts the extraordinary circumstances that led to the finding of the map and, nearly three years later, is still giddy over its details and Raynor’s strategies. (His enthusiasm is also a running joke within his family: “You’re really talking about the map again,” his wife says.) But mostly, Manthey talks about the new Midland Hills, why it’s so improved, why he’s so proud of it and how excited he is for members to finally play it. He talks about the sacrifice they made to give up their golf course, especially during an unusual summer like this one when golf rounds spiked. He thinks they’ll be blown away.

“The thing I’m most proud of,” Urbina says, “is the involvement of the superintendent and his willingness to go the extra mile to make sure that history was, to the best of our ability, reborn. The membership, they knew what we were working on, and the GM, Tim Ivory, he was great support. But what I’m most proud of is the superintendent’s love-affair with the golf course he works on every day and realizing its place in Golden Age architecture.”

The restoration was finished in mid-November, just as winter weather started to arrive. All that’s left to do is clean up some construction scars. The new front nine will debut in the spring, with the back nine opening a week or two later.

Some members have toured the course since it closed, and a handful were there just last week, walking in groups of two, pointing to removed trees, staring down new sightlines and inspecting greens. If you looked closely, through the glare of the midday sun, and followed their eyes, you could almost see them reading putts.