At the WGC-FedEx St. Jude Invitational, Memphis golf history is just a few feet from the first tee

By Mark Giannotto, Gannett News

They were standing at the fence line as Bubba Watson, Brandt Snedeker and Paul Casey stood ready to tee off their practice round Tuesday morning. This is where Dave and Nancy Wells live, adjacent to the tennis courts, with a backyard overlooking the first hole at TPC Southwind.

So on the first day reporters were allowed at the first fan-less World Golf Championships-FedEx St. Jude Invitational, Dave Wells was one of the few Memphians doing exactly what he would have been doing if the tournament hadn’t been completely altered by the coronavirus pandemic.

He was watching the world’s best golfers, and none of them could have possibly known that the history of professional golf in Memphis sat right up the hill from that first tee box.

“I’ve got a museum of sorts on my second floor,” Wells said. “Do you want to come inside to see it?”

Tee times | TV | Photos | Odds, best bets | Fantasy picks

The scene this week at the Memphis area’s annual PGA Tour stop is strange. There are no grandstands. There are no concession stands. There is no buzz. Just the hum of a few generators, and the cascading sounds of pool water filtering from some of the homes in this exclusive neighborhood. About the only familiar face running around the grounds is Millie, the well-trained dog of TPC Southwind course superintendent Nick Bisanz.

But Dave and Nancy Wells are here, even if this is all a bit odd for them, too. Nancy has been volunteering at this tournament since it was the Danny Thomas Classic at the old Colonial Country Club. She started as a walking scorer and, in recent years, worked at the information desk.

“There’s no one to inform this year,” she said. “It’s kind of a shame.”

So this will be unprecedented for unfortunate reasons, which also means it might just need a place in the room Dave Wells, 82, turned into an homage to the game he loves.

The son of Memphis Amateur Sports Hall of Famer Buddy Wells, who oversaw Crump Stadium and then Liberty Bowl Memorial Stadium for the city, Dave Wells retired almost 30 years ago from his job at Schering-Plough. And even then, when someone would ask what he did for a living, Wells would joke, “I play golf.”

“The business relationships, a lot of it had to do with golf,” he explained.

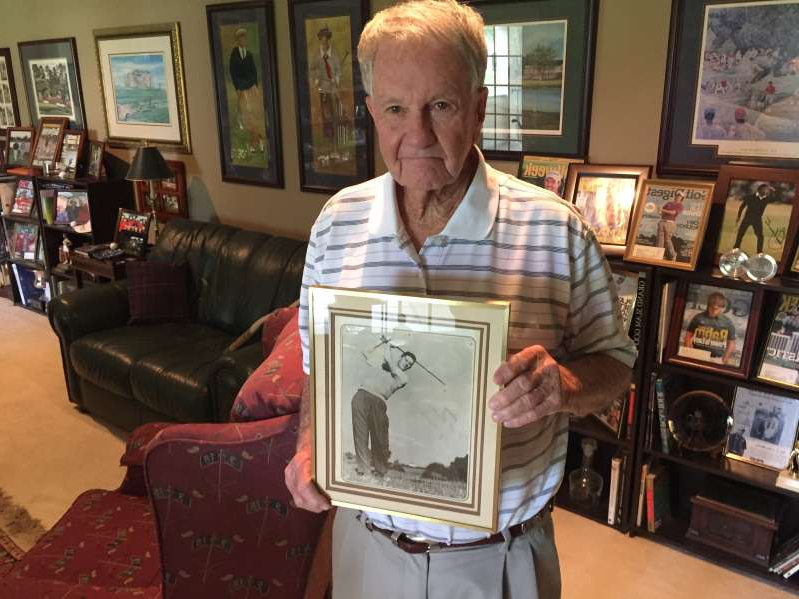

Dave Wells stands in front of one of the many bookshelves filled with golf memorabilia inside his house next to the first tee box at TPC Southwind. Photo by Mark Giannotto/The Commercial Appeal

It means almost every inch of almost every wall of this “museum” is filled with golf memorabilia from seemingly every significant golfer of the past century. Sam Snead. Ben Hogan. Arnold Palmer. Jack Nicklaus. Lee Trevino. Seve Ballesteros. Tom Watson. You name it, aside from Tiger Woods, Wells probably has an autograph up somewhere.

There are also golf clubs from 1924 and golf balls commemorating rounds at the golf’s greatest courses, or holes-in-one, or times when Wells shot his age.

But it’s the pieces of Memphis golf lore that feel so important, particularly this year when most of Memphis can’t be here.

There’s the Ben Hogan signature, which prompts Wells to tell the story of how he once met Hogan at old Cherokee Golf Course at the corner of Lamar and Prescott. There’s also an autographed picture from Al Geiberger with this note: “You were here that great day.”

That great day is, of course, the day Geiberger shot a 59 at Colonial Country Club back in 1977. Wells was there, and he was there in 1965 when Jack Nicklaus won in Memphis.

“You would bring a chair and stand on it so you could see over the people in front of you,” Wells said.

There’s the faded program from the 1979 Danny Thomas Classic that his son used to get autographs. When they came home, Wells asked how many he managed to get. Three, his son said. It was only a few years later, when Wells leafed through the program in his son’s room, that he realized who those three autographs were from.

Gerald Ford, Bear Bryant and Danny Thomas himself.

There’s a poster from the 1985 tournament that notes the purse for the entire event was $500,000. Last year, the top three finishers at the WGC-FedEx St. Jude Invitational all earned more than that. This year, the total purse is $10.5 million.

On another shelf sits a photo of Patrick Reed from when he won an American Junior Golf Association event at TPC Southwind as a 14-year-old.

Another prized possession is a signed picture from Cary Middlecoff, the greatest Memphis golf product. It’s the first piece of memorabilia Wells ever got. It’s from 1948.

There’s also a Masters scrapbook that sits near it, with Palmer’s impeccable signature. Wells had it signed when he played a round with Palmer at Bay Hill decades ago.

“Arnold Palmer told me the most important thing about the game of golf is who you meet on the golf course,” Wells said.

And so for a little while Tuesday, walking around that second floor room full of magazine covers and photos and balls and clubs, this year’s tournament felt a little like every other PGA Tour event this city has hosted. Because the best part of this tournament is rarely the golfers. It’s the Memphians, be they fans or volunteers, who you meet.

It’s people like Dave Wells, leaning against his fence watching the world’s best tee off in his backyard, just a few feet away from Memphis golf history.

Dave “Iron Byron” Wells, Nut #2803, is a legendary member of the Golf Nut Society. He earned thousands of points for this story and all that was revealed within. – The Head Nut #0001