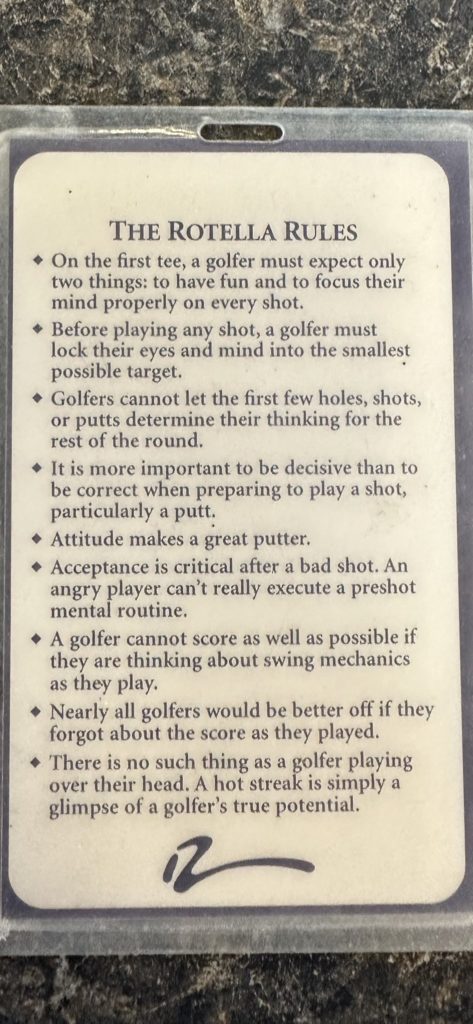

Speaking of Bob Rotella…

The Head Nut

#0001

Speaking of Bob Rotella…

The Head Nut

#0001

This is incredible, a one-hour interview that gets better the longer it goes…

The Head Nut

#0001

This is an amazing FYI for my golf buddies who have played Settindown (and several who haven’t yet). This guy is a great guy and a great player. He played for Harvey Penick at Texas with Tom Kite and Ben Crenshaw.

He’s the greatest golf ball hunter I’ve ever known. He finds balls as he plays to his scratch handicap and doesn’t slow down his group. His MO is if you give him an egg carton and tell him your preferred ball he’ll give you a dozen. All of the Settindown regulars find numerous balls but this guy is the undisputed king. – Rick Eaton

By Alan Thielemann, Ansley Golf Club, Settindown Creek, Roswel, GA

Thanks for all of you putting up with me looking for balls this year, I realize I drag behind the group at times looking. New record of 3,150, which I doubt I will ever have the interest in duplicating. Here is the answer to some of your questions I often get asked.

1. Most brands found – Titleist ProV1 by a long shot – followed by Callaway Chrome Soft, Kirkland, ProV1X, Srixon, Taylor Tour Performance, Taylor TPX and TP, AVX, Vice, Snell, Bridgestone

2. What percentage are NOT keepers – Depends on how many I reject on the course, but about 15 – 20% end up in the recycle buckets. A lot are good balls, but with a scuff mark… I don’t pick up Titleist Practice Balls, which I find a lot of!

3. What percentage are good, but categorized as “others” (not big brands) like Bridgestone 812, Titleist Velocity, Titleist tour soft, Callaway Super Soft, Pinnacle, Kirkland, Maxfli, Nike, etc. – 25%

4. What brand name balls are least desired ? Callaway Chrome Soft (some with stripes, some not), Srixon, Pink, Red, Green and Orange name brand balls.

5. What percentage are brand name balls, but not good enough to get egg carton status? (off color, minor blemish, too old..) 5%

6. How do you clean them? When I get a big batch (50 or more) at one time, I use a brush attachment on an electric drill. But mostly I use a ball washer, scrubby pad and occasionally bleach. Takes about 1 minute per ball on average.

7. So how many were given away this year?

20% rejects

25% other brands, not desired by male golfers

5% others

So a little over 50% make it to egg cartons and are given away. (by the way, thank you all for your egg cartons. Last request brought in about 30, so I don’t need any now.)

50% of 3,150 = 1,575

1,575 divided by 12 = 131 dozen

For sake of discussion, everything I give away I try to have them be Grade A, which sells used for about $35 – $40 a dozen. So my guess is that I gave away about $4,500 worth of balls! That said, I love finding them and love giving them away.

I wish you all a very Merry Christmas, and shout if you need balls!

Alan

—–

Golf Nuts come in all shapes and sizes. 🙂

The Head Nut

#0001

Hey Nuts,

I just received the following note from #3194…

Dear Head Nut,

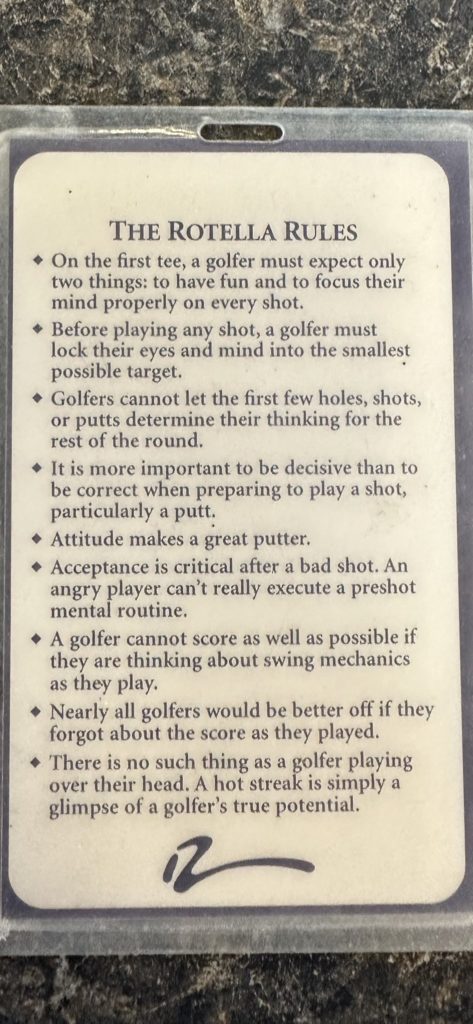

I finished my book “Tee to Green: A Golfer’s Odyssey through America’s 50 States.” It is available on Amazon and will be on Barnes & Noble next week!

Here’s the Amazon summary…

In this captivating journey, golf enthusiast and author George Stark takes you on a memorable road trip through all 50 states, showcasing the incredible diversity and uniqueness of golf courses from coast to coast. From iconic, world-renowned courses (Sand Hills, Kiawah Island) to hidden gems off the beaten path (Fox Run, Bully Pulpit), every state holds its own tale of challenge and charm.

Check it out Golf Nuts. Perhaps Santa Claus would like to give it to you for Christmas.

The Head Nut

#0001

Dear Head Nut,

It’s funny, whenever I book a tee time at different courses, not one person has made a remark or taken notice of my name, so I’m honoured that you love it, and that other golf nuts would too. I was born and raised in Prince Edward Island in Eastern Canada, just up the road from Maine and it is a fairly common name back there, believe it or not…

Oddly enough, up until last year, I worked many years as a Driver for a few companies, so there’s that twist too! No wonder I’m conflicted a lot of the time! 😉

Mike Wedge

Well, how about that? Mr. Wedge…The Driver.

“Honey, your new putter just arrived. It was delivered by the Driver, Mr. Wedge.”

The Head Nut

#0001

(Yes, that is his name…he’s a natural!)

Hi there,

I stumbled onto your site while perusing various golf articles online and am happy to see that your site exists! I’m wondering if you allow international members, I’m Canadian and although being new to the game at the age of 60 (I did play a few rounds when I was a young guy but it never took hold) but earlier this summer, I acquired a set of clubs that were being given away… They were awful clubs, so I started buying different clubs cheaply online and at local thrift stores and started hitting the local courses here on mid Vancouver Island.

Since the end of June of this year until now, I’ve shot approximately 60 rounds of golf on par 3s, executive courses, and on full courses as well and I did the math the other night, it works out to a round every 2 ½ days… I am now a member at the lovely Comox Golf Course here, a winter membership that I’ll be extending to a yearly one in the next while… I also got fitted for clubs in late August and have been enjoying my new clubs even if my handicap remains high, there’s something new to learn everyday on the course and every once in a while, an epiphany too…

Anyhoo, how would I, as a Canadian, go about joining you and your esteemed colleagues’ society as I believe and readily admit to becoming a golf nut in a fairly short period of time, in my opinion anyway… I’m also a musician, and now anytime there’s a gig out of town, my clubs make it into the car with my bass guitars… On a serious note, I’m the sole caregiver for my elderly mom, and this wonderful game gets me out of the house for a couple of hours and is a godsend in terms of its destressing and generally calming nature, and mom tells relatives that there’s now a golfer in the family (she hasn’t seen me play lol) …Also, with my last name, which I promise I was born with, I think I should be a shoe in!

Thanks for your time, sorry to write a novel and I look forward to your reply, whether it’s before or after tomorrows tee time!

Best Regards,

Mike Wedge

Howdy Mr. Wedge,

Of course, we allow Canadian members in our august society. We don’t even require a passport. We have members worldwide, and besides, how could we call ourselves the Golf Nut Society if we disallowed anyone named “Wedge”?

Welcome aboard!

The Head Nut

#0001

“This is #17 at Cypress Point in December 2021…wind was blowing near 70 mph and rain most of the day. Most insane day of golf any of us ever had and the caddies had never seen it before either. My tee shot drifted at least 150 yards left.” – Gavin Blair

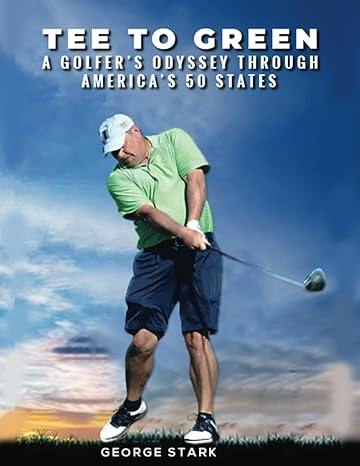

Not to mention that every one of those swing keys is dead wrong.

Go Nuts!

The Head Nut

#0001